Contention ratio, who's go is it anyway?

In a previous blog, How much data does the UK consume in a second, we eluded to the fact that although a broadband connection is sold as X megabits per second achieving this will depend on what else is happening on the network at the time.

The Internet works in much the same way as the household mains water system. Growing up I remember switching on all the taps in the house for the amusement of the one highest and furthest from the source drying up (poking cowpats with a stick was another game to while away the hours!). The point is that the ability to deliver the advertised data-rate (think water pressure) depends on the competition for the network or contention to use the correct term. Another analogy is that of cars using a road. When traffic is light they can all use the road simultaneously and drive at the speed limit. Come rush-hour this starts to break down because to many cars are trying to use the same road simultaneously. Eventually they all get from A to B but it takes longer.

Our patterns of data usage mean that generally we can share the network without noticing any particular degradation of quality to that which we were expecting. Consider what happens when sat browsing a website. We make a request for a webpage which is then returned all normally within a few seconds. In general we then sit and read the page for a while before clicking on a link and repeating the process. So although our connection needed to deliver the page quickly, the speed was only required for a short period of time before being idle again. In this idle time other users will be using their broadband connections but its possible to see that so long as there are enough users bundled together they can all have a highspeed experience without the necessity of infrastructure to support them all simultaneously.

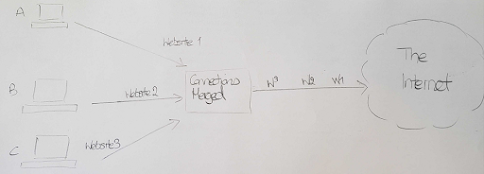

There are examples of different traffic patterns of course, streaming a film being a good one. Early implementations of media streaming relied on being able to achieve a constant connection speed to ensure the film played without the classic 'buffering' messages. Most modern streaming platforms use systems whereby they will grab chunks of a film as required pre-empting what it going to be required next. This is more reliable and possible because the speed at which broadband connections work is far in excess of the speed needed to stream even HD content.The consolidation of Internet traffic happens at many levels from the street cabinet, through regional data centres and up to international exchanges. The rate at which these links are consolidated is called contention ratio. As an example if 10 households had a 10Mb/s connection and these were merged into a link that had a speed of 20Mb/s this would be a 5:1 contention ratio, (10*10)/20.

Why have contention at all? Really this comes down to money and practicality, contention ratios can be improved but it comes at the cost of more infrastructure and practically the amount of equipment and space required would just become impractical for no real gain.

In the UK the telecoms regulator OFCOM requires that everybody have the right to a connection with a contention ration of no more that 50:1 under the Universal Service Obligation (basically your right to have access to the Internet).

As an side traditional telephone calls didn't work in this way, they required a unique connection between every active caller but if you consider the way a conversation works in that only one person speaks at a time this method of connecting them means that one direction of the call is essentially idle and therefore wasted 50% of the time. Moving telephone calls to use Voice over IP technologies (VoIP) greatly reduces this problem.

To sum up, the Internet relies on us not all using it at the same time and in the same way so that it can provide a good service to all at a cost that doesn't break the bank.

Comments

Post a Comment